What Is the Social Model of Disability and Why Do I Use It?

Many disabled people — whether they realize it or not — first become acquainted with the medical model of disability, usually once a health care provider gives a diagnosis. It says people are disabled because of how they differ from other members of society, or according to their diagnoses or impairments.

Individuals using the medical model of disability see me as someone with cerebral palsy due to a birth injury. That disability primarily affects my mobility, movement, balance and muscle flexibility. However, the main advantage of having a disability from birth is I’ve learned to live with it quite well. I use a mobility aid to walk, but in general, have a satisfying life where my disability largely does not affect me from day to day.

Then, there’s the social model of disability, which says societal barriers are the disabling factors, and not someone’s diagnoses or differences. I significantly prefer the social model of disability and heartily agree with it. That’s not the case for everyone, though, and people should feel free to use whichever model works best for them.

My disability is not a major detriment to my life. That could change as I get older, but I know how to manage it. However, nearly every time I leave the house, I face societal barriers that make it difficult, unpleasant, upsetting and frustrating to participate in everyday life. I’m far more affected by people’s perceptions of my disability than the disability itself.

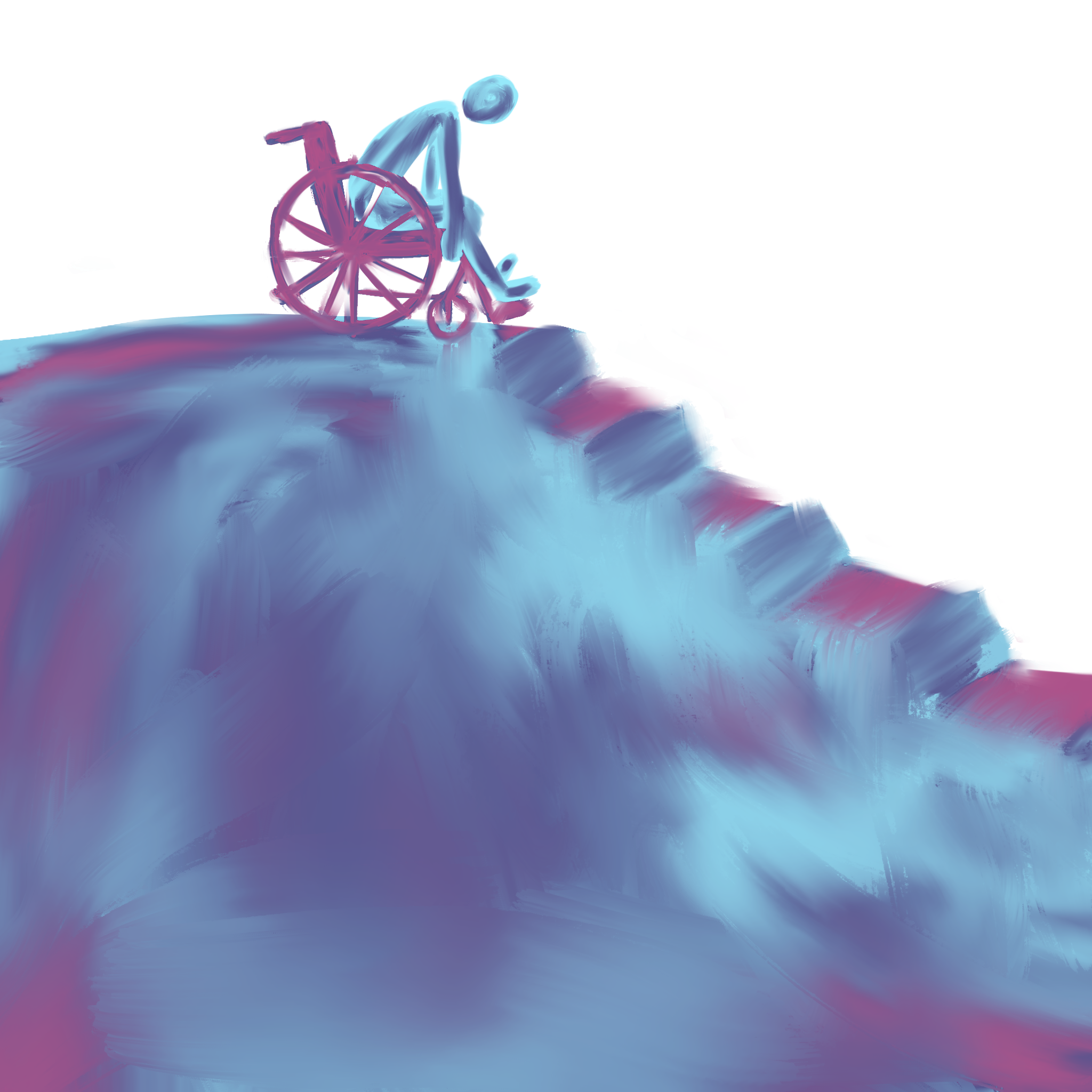

Illustration by Malachi Arsac

Examples of Societal Barriers

Societal barriers can take many forms. However, the ones I most commonly encounter are:

Building inaccessibility or poor infrastructure (stairs, curbs, broken elevators or automatic doors)

People’s assumptions about what disabled people can or cannot do

Strangers believing they have the right to know about disabled people’s private lives

Negative, misguided or incorrect attitudes towards disabled people

Illustration by Malachi Arsac

What Does the Social Model of Disability Try to Achieve?

The social model of disability’s goal is to remove the barriers that make life harder for disabled people. If that’s not possible, the next best thing is to raise awareness of those obstacles and help the wider population understand the need for collective improvements. The social model of disability also focuses on meeting individual needs through relevant support.

On the other hand, the medical model of disability tries to fix what’s “wrong” with a disabled person, usually with treatments or medication. I’ve often dealt with doctors who wanted to address parts of my disability that were not causing any issues, but were, nonetheless, seen as abnormal and worthy of scrutiny.

I’m not at all against treatments when they’re warranted. I spent more than 15 years of my life doing intensive, daily physical therapy. But, I don’t view my disability as a problem to fix. It’s a part of me, and my goal is to participate in life as fully as possible within the limitations my disability poses.

Illustration by Malachi Arsac

How Can People Prioritize the Social Model of Disability?

Removing society’s barriers for disabled people is a lifelong effort. However, there are some things everyone can do to work for progress.

Listen to Disabled People’s Perspectives

My interactions with others would be so much easier and less stressful if people listened to me more rather than making quick assumptions. I frequently get worn down because it seems others immediately view me as incapable or less capable than themselves. It typically takes me years of regularly being around someone before they’ll stop immediately assuming I can’t do things or need help.

Sure, there are a lot of things I can’t do, but I’m also excellent at adapting. I might not do something the same way you do, but there’s a good chance I can figure out a safe and effective alternative. And if I can’t, I’ll ask for and accept help.

When getting to know new people, I talk to them about how I’m extremely aware of my capabilities and limitations and will ask for help when needed. However, I also love being as independent as possible. It’s very annoying when someone asks me if I need help and I politely decline, but they insist on assisting anyway. Such interactions probably make the other person feel they’ve done something nice, but they’ve taken away my independence instead.

Get Disabled People’s Advice Before Making Decisions

The people who don’t experience barriers are less likely to see them until someone affected points them out. A particularly unforgettable example happened more than a decade ago when I was trying to get to work after a heavy snowstorm.

I stepped off the bus at my stop, but while crossing the street to get to my office, I noticed whoever had plowed the snow had piled it in such a way that it blocked a curb cutaway I’d ordinarily use when crossing the street.

I was able to improvise and find a different option, but other people might not have had that choice. Whoever decided to handle the snow like that probably never realized the problem they caused. But anyone who needs to use the curb cutaway would have immediately noticed the issue and could have given useful input.

Respect Disabled People’s Right to Privacy

My openness about my disability brings out some interesting reactions in people. Many think I don’t want to talk about it, though their curiosity becomes obvious to the point of extreme awkwardness.

I don’t mind talking about my disability and would prefer doing that because such conversations give me opportunities to educate people and dispel incorrect assumptions. However, I’ve had some jarring encounters where strangers think my disability gives them the right to know everything about me.

Once, I was sitting on the bus, and the older man beside me noticed my mobility aid. He openly stared at me for a while before finally blurting out “So, can you have sex?” I told him it was none of his business and made it clear I would not engage further.

Little did he know that, while I can have sex, I’m asexual, and as far as my position on the spectrum goes, I’m not interested in sex whatsoever. But, a stranger doesn’t need to know that, and shouldn’t have asked about my sex life.

Understand the Value of the Appropriate Support

I’ve found societal misconceptions around disability are assumption-driven. People are quick to assume I can’t do things, but they don’t stop to think about how support, and the reduction or removal of barriers, could make a gigantic difference in my daily existence.

The best job I ever had was working at concerts, festivals and other large-scale events. The work was fantastic for a music fanatic like me. But, the company owner was the most empowering part of the whole experience.

He has a son with cerebral palsy, and from the moment we met, the owner told me he knew from living with and raising his son that I would know best about what I could and could not do. So, he promised to listen to me and never doubt my assessments of particular assignments.

The work involved standing for several hours at a time — often outdoors and in bad weather — and frequently required dealing with grumpy, intoxicated event attendees. However, the company owner, and all supervisors under him, always treated me the same as my colleagues and never said things like “Are you sure you’re up for this?” They knew I would mention if I needed to take a less strenuous role and trusted me to be honest about my abilities and limitations.

Illustration by Malachi Arsac

I’m a Human, Not an Inspiration

One of the downsides of having a very visible disability is that strangers frequently say things like, “Oh, you’re such an inspiration!” despite usually not knowing anything about me. I understand they’re trying to be encouraging, but I never know how to respond. In their view, the mere fact I’m interacting with society inspires them. But, I’m just trying to live my life and go about my business, the same as anyone else.

When people fixate on my disability, that’s a barrier in itself. It throws me into a constant, unwanted battle to get them to see me as a human who happens to have a disability. The most fulfilling experiences in my life have been when others see my humanity first and foremost, viewing the disability as just one aspect.

I greatly appreciate it when someone takes the time to get to know all of me. Then, we have the best chance of getting to a point of mutual understanding and working together in dismantling society’s barriers that create obstacles for myself and others with disabilities.

Illustration by Malachi Arsac